Those of us Burmese who have made overthrowing our country’s well-entrenched military dictatorship, our business – or Doe-Ayay, as we say in Burma in specific reference to protests against any Oppressive Order – do not look to the United Nations or the European Union, let alone the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), for help. Nor do we seek advice from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, or any New York or London-based human rights mafia. We strive to “breath through our own nose” as have many others before us who broke free of the bondage in which they found themselves.

For instance, Frederick Douglass, the famed 19th century slave who escaped slavery and became an iconic African abolitionist and left a body of inspiring words, quotes and writings including the following: “Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet deprecate agitation, are men who want crops without ploughing the ground.”

But in ploughing our own ground, we knew we needed to seek advice and assistance from those who were proven successful as ‘regime changers’, pre- and post-9/11.

Before the toppling of Saddam Hussein, following the World Trade Center attack in New York, I briefly met, by chance, James Woolsey, former director of the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) from 1993 to 1995 and one of the earliest advocates of the non-UN-authorised US Second Invasion of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. I met Woolsey, no longer at the CIA, at a close American friend’s private party in Washington DC.

I was introduced to the veteran spook-master by my host, the late W. Scott Thompson, a well-known ‘defence intellectual’ in Washington who was a White House Fellow at the Reagan White House. Ex-son-in-law of Paul Nitze, Ronald Reagan’s chief negotiator on nuclear arms reduction with the Soviet Union, Professor Thompson was one of the best-connected Washington insiders I knew. In his own right, Scott was also a Professor Emeritus at Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University and served as a founding board member of the United States Institute of Peace.

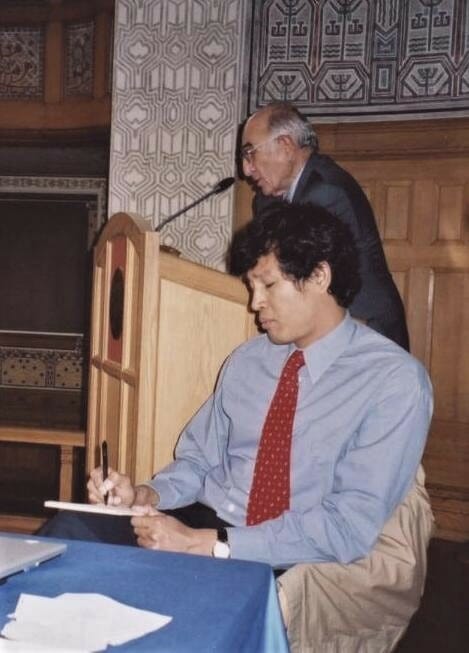

Zarni with the late professor W. Scott Thompson (in blue tie) and his son Nicholas Thompson, at the latter’s wedding reception, New Hampshire, Fall, 2002

Originally a specialist in African affairs, Scott later shifted his research and scholarly interests at Fletcher School to Southeast Asia through which he encountered some of the region’s leaders including Fidel V. Ramos, former President of the Philippines, who played an instrumental role as Chief of the Philippine Constabulary in the 1986 overthrow of the dictator, Marcos.

Scott’s friendship with President Ramos proved invaluable to me as I sought strategic advice from anti-Marcos generals who personally knew Burma’s dictators and spent time with the latter in Manila and Rangoon.

In the next essay in this series, I will say more about my late, wonderful friend who played an enormously helpful role in my attempts at strategic engagement with Myanmar’s intransigent military.

Suffice it to say, in my fleeting intimate party conversation with the great spook and regime-changer, I cut to the chase, and asked him, “what is your one piece of advice for us Burmese dissidents on regime change in our country?” Sufficiently informed about the affairs of Burma, next to China, the Yale-educated-Rhodie-cum-spook was equally direct in his reply without a blink: “You are going to need a lot of $$!” He was not joking, and I knew it.

What do you do if you are a semi-poor start-up academic, who did not have “a lot of money”, nor cash access to deep pockets? By the early 1990’s, George Soros had set up a ‘Burma Project’ as the result of his friendship with a Maryland-based Burmese oncologist and inventor named Dr Myo Thant, who happened to be Aung San Suu Kyi’s distant cousin. Housed within the then Open Society Institute or OSI, Soros’s Burma Project came into existence just a year, or so, before the UN General Assembly established the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Myanmar, in 1994. But Soros’ money was not for the regime change, but for opening-up closed societies (repressed social orders).

Undaunted, I reminded myself of the Burmese proverb which my late father used to invoke when I was growing up: “Birds die flying, men die plotting”.

Zarni with his great uncle the late Zeya Kyaw Htin Lt-Colonel Ant Kywe at the latter’s home in Rangoon, Nov. 2005.

In the absence of “lots of money” – Soros’ or others’ – for the regime change in Burma, plotting was exactly what I set out to do. While keeping my first-real day-job, as an assistant professor of education in a teacher education university in Chicago, I pursued my real job of seeking help from others who knew better than I, about the nitty-gritty, or the mechanics of dislodging well-entrenched criminal regimes, such as the Marcos dictatorship.

As I wrote in my previous essays, I had reached my own personal conclusion about Aung San Suu Kyi’s leadership, or lack of it, and learned about the unpalatable truth about Washington talking the talk of supporting the Burmese democratic movement, while failing to walk the walk. As early as the Spring of 2003, when she, (Suu Kyi), escaped narrowly what was made to look like communal violence between the military’s supporters and the NLD campaigners, near Depayin town, north of my home city of Mandalay, I had decided that the NLD leader was in no position to change the regime.

Matt Daley, the then Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, with a group of Burmese dissidents in exile, at the home of Dr Marjolaine Tin Nyo. Chesapeake Bay, Maryland, USA, July 2004

The few one-on-one meetings I had with Matthew Daley, the then Deputy Assistant Secretary of State in the US Statement Department, in 2003 and 2004, helped me advance my own thoughts around Burmese affairs insofar as grappling with the question of: “What needs to be done?” That perennial question which has confronted all revolutionaries and radicals since the days of Lenin.

Accordingly, I made a radical shift – from being staunchly pro-sanctions within Aung San Suu Kyi’s pro-sanctions camp, which had become heavily reliant on Western policy support and media cheer-leading, to my own paradigm of what I called, “strategic engagement”, that is, talking to the ‘Enemies of the People’, namely, the Burmese generals, with the ultimate goal of triggering an implosion.

An important, but brief, detour here about the context may be in order.

Emphatically, strategic engagement must not be misconstrued as ‘constructive engagement’ which became the buzzwords for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ largely business-as-usual interactions with the military regime which called itself SPDC, in those days. The SPDC was shunned by new western investors as the result of the 1997 US and EU sanctions and further US sanctions in 2003 – although the sanction regimes conveniently exempted the West’s gas and oil corporations such as California-based Unico-Chevron and Paris-based Total, as I pointed out in Part 2 of my essay series.

Naturally, the SPDC generals were eager to woo Asian investors who, unlike their western counterparts from PepsiCo, Levi, Heineken, etc., would typically not ‘fuss’ over things like crimes against humanity, including forced labour, summary executions, arbitrary arrests, sexual violence, in various regions of Burma including Rohingyas in Rakhine, Karen and Shan in Eastern and Southern Burma, and pro-democracy dissidents in the heartlands. Nor did Burma’s neighbourly investors from top-tiered ASEAN countries (such as Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia), Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, Japan, S. Korea raise any issue about the absence of labour rights for the Burmese workers in the newly established garment industry, natural resource extraction sector, construction and so on.

Professor David Steinberg and Zarni, The bi-annual Burma Studies Conference at Gothenburg Sweden 2002

Investment in Burma’s ‘frontier economy’ was presented as a form of constructive engagement. This was in addition to fast-tracking Burma’s membership into ASEAN and subsequently including Burmese generals who held virtually all cabinet posts and presided over the Burmese Way to Crony Capitalism. Using such Orientalist discourse as ‘Asian Values’, ASEAN’s iconic leaders such as Lee Kwan Yew and Mahathir Mohammad would also shield the military regime from the constant barrage of attempts in international fora at putting diplomatic, media and political pressure on their new-found ASEAN (business) partner. Under ASEAN’s Constructive Engagement, literally anything goes insofar as the Burmese regime’s conduct, domestically.

By the time Burma was admitted to ASEAN in 1997, Burma’s military regime had already been subject of recurring condemnations by the UN and other human rights watchdogs. Burmese generals were committing international crimes including war crimes, and crimes against humanity, against Rohingyas, dissidents from the popular National League for Democracy party of Ms Suu Kyi and the country’s national minorities such as Shan and Karen. In effect, ASEAN’s Constructive Engagement held the grouping’s collective nose, no matter which egregious (often documented) crimes were perpetrated by the regime.

Set up and run by autocratic regimes across Southeast Asia, this regional association of UN member states clearly adhered to the absolutist notion of state sovereignty, established in the Prussian state of Westphalia in the days of feudal Europe. The Westphalian model permitted warring feudal rulers to do anything they pleased, or deemed necessary, to the subject populations in the territories the rulers controlled, as long as their “domestic” conduct did not disrupt the inter-kingdom trade and diplomatic relations. The ASEAN leaders ‘disregarded’ the idea of human rights and politely brushed aside concerns about political repression and rights violations raised by Western liberal democratic regimes as nothing more than empty polemic at best, and with intolerable hypocrisy.

To belabour the obvious, ASEAN was set up as a geopolitical group against the Communist threats in Southeast Asia in the wake of the Vietnam war. It has never been a champion of human rights, or the civil and political rights of 500 million inhabitants of the 10 member-states, but came to redefine itself as a regional bloc, pushing for economic development and integration of the nation-states in the region post-Cold War.

The painful truth was neither side – not the West’s ‘sanctioners’, nor the Asian ‘Constructive Engagers’ – were really advancing the interests of the wretched of Burma.

In sharp contrast, I for one viewed a more strategically nuanced type of engagement that had an uncompromising focus of driving a wedge between the existing power rivalries inside the military as a large bureaucratic organisation, with its own turf wars and conflicts of personal interests and personalities. It is this logic – and against the backdrop of no real help from any external actor – that propelled me to turn to the veterans of the successful anti-Marcos ‘People Power’ revolt of 1986, specifically ex-General, and President, Fidel V. Ramos, and his former head of the military intelligence services, Joe Almonte.

Fidel V. Ramos,the then President and ex-General, the Philippines, (second from the far right) and his National Security Chief ex-General Joe Almonte, seen with Burmese generals Than Shwe, Maung Aye and Khin Nyunt, Rangoon Ministry of Defence Golf Course, (Photo courtesy of President Ramos), Oct. 1997. Ramos visit (to Myanmar) cements new Asean ties: https://www.burmalibrary.org/

Besides having come from an extended military family with cousins, uncles, great-uncles, and male and female in-laws, in various branches of the Tatmadaw, or the military, my PhD research, to a considerable extent, examined closely the inner workings of the ruling Burmese military. I did so through in-depth interviews with former ranking members of the 1962 coup, which established the military dictatorship, as well as some of the former military officers who attempted an abortive regime change, from within, in 1976.

Perhaps equally important, I was cut from the same nationalistic, militarist cloth as any Burmese military officer, senior or junior. In fact, I was admitted to the Officers’ Training Corp in 1979, which recruited high school graduates at the age of 16, or 17 years.

Equipped with the vocabulary of militaristic patriotism and specialised knowledge of the top echelon of the military institution, I felt rather comfortable in formulating this ‘strategic engagement’ approach. However, I was in uncharted waters, and my approach, wholly un-tested, the subject of the next essay.

Maung Zarni

FORSEA